Egle's Painting

Egle Karlonaite

Lithuania based abstract artist, Egle Karlonaite, has been developing her skills in creating art for interior design industry worldwide for the past several years. She blended her passion of interior design with abstract art bringing the harmony to the space one is designing. Egle strives to create a “wow” feeling and evoke her viewer through lights, intensive color contrasts & use of gold’s . Her creative process is inseparable from showcasing freedom: uneven geometric forms, running paint fast brush strokes.

Concentrating on non - objective themes allows the artist to leave the space for one’s imagination. Traveling, passion to design and architecture formed her painting manners and the way she views the world. Today most of her artworks are sold to private collections in the USA, Singapore, United Kingdom, Ireland, France and Italy. Artist was featured in House and Garden UK, recognized as a finalist at The Second Global Art Awards 2018 and successfully exhibiting her work in prestigious art events worldwide.

Adrian Ghenie - THE SECOND PRESENTATION ROOM

Inside Adrian Ghenie’s shadowed room, forces of brutality and beauty coexist. There is riveting painterly evidence of Ghenie’s physical assault on the canvas, where he has attacked the surface with loaded pigment using his palette knife to carve sensuous arenas of visual expression. On the richly textured surface, there are breathtaking accretions of color, startling chromatic contrasts, and textural flourishes rendered with extraordinary intensity. Drawing upon Baroque chiaroscuro, Ghenie's monumental 2011 painting The Second Presentation Room is cloaked in theatrical immanence and claustrophobia, heightened through the sumptuous passages of inky purple, dark olive green, and burnt crimson. A bold testament to Ghenie’s celebrated mastery of spatial composition, seductive textural quality, and compelling visual appropriation of allegorical historical references, The Second Presentation Room exposes the apotheosis of the artist’s creative genius.

The direct source employed by Ghenie for The Second Presentation Room is El Lissitzky’s Kabinett der Abstrakten, the Russian Constructivist's installation room conceived in 1928 for the Landesmuseum in Hannover. Lissitsky’s Abstract Cabinet represented the modular, organized theoretical framework of Constructivism, which called for a new form of art in the service of social revolution. As first espoused by Vladimir Tatlin in 1913, Constructivism rejected the autonomy of art and cultivated a method of thought that fused art and industrial functionality. Such fusion is clearly articulated by Lissitzky’s visually integrated presentation room, which emphasized the immaculate organization of space and the unadulterated purity of all art contained within that space. Appropriating Lissitzky’s iconic room, Adrian Ghenie interrogates the hopeful ideology of the fledgling socialist revolution. As Mark Gisbourne writes, “The pristine world of utopian constructivist ideas of clarity and definition have been despoiled and violated; a sort of Baroque ruination and set of surface accretions have taken their place. But it is intended less by the artist as a banal commentary on the lost utopian hopes of a revolutionary modernism, but rather on the claustrophobic nature and eventual material stasis that inevitably flow from preordained ideologies.” (Mark Gisbourne, “Baroque Decisions: the Inflected World of Adrian Ghenie” in Juerg Judin, Adrian Ghenie, Ostfildern, 2014, p. 28)

In Adrian Ghenie's childhood, Romania was ruled by Nicolae Ceaușescu’s tyrannical Communist regime; a period of severe political oppression and unrest that has significantly informed Ghenie's work. The Second Presentation Room discloses Ghenie’s personal history through aesthetic reference to his acute sensory memories from childhood, characterized by “the dirty and grubby surface textures of his father’s garage and cellar, his grandmother’s roof and garden, or his brother’s garage containing various detritus.” As Gisbourne observes, Ghenie first saw these spaces as “messy and untidy but texture-laden surroundings of shabby objects, broken furniture, rotting food and apples...yet they have come in retrospect to summarize in his mind a certain perception of his childhood.” (Ibid., p. 29) In the present work, Ghenie fuses aspects of his personal history with events from national history. Although he borrows from Lissitzky and from his private memories in order to interpret--or make sense of--the collective public history to which he belongs, in the end Ghenie constructs something far more powerful than the historical referent or his intimate personal consciousness. Ultimately, Ghenie conceives The Second Presentation Room on the basis of past realities, blending both ‘public’ and ‘private’ histories together, and then distorting these realities through the lens of his own fictive imagination. Conceived through Ghenie’s tactic of distortion, there is a palpable tension manifest in the present work between the real and the imaginative. Ghenie articulates this dichotomy through the oscillating spillages of representation and abstraction, fomenting a narrative that revises and even fabricates what we know to be real.

In the shifting perspectival planes of the present work, areas of recognizable imagery yield to swathes of pure abstraction. Deploying a wild gestural abandon through cyclical overpainting and excavation, Ghenie constructs a claustrophobic aura that underscores the metaphorical significance of the enclosed room. In the present work, the room not only functions as the physical setting, but a psychologically-inflected room of haunting human memory. Rather than alluding to a world beyond, The Second Presentation Room is a self-engendered entity, a cavernous emblem of the enveloped psyche. Vandalized, fragmented, and broken, the room capitulates and gives in to itself, subsiding and crashing into the picture plane like the collapsed ideology of a once-hopeful social revolution. It is this quality of self-effacement and visceral power, as rooted in both historical and personal reference, that renders The Second Presentation Room one of the most poignant works in Ghenie’s oeuvre to date.

Jean-Michel Basquiat- SANTO 4

“The work Basquiat began in late 1982 signaled a new phase of intensity and complexity that focused on black subjects and social inequities and incorporates a growing vocabulary of popular images and characters…The effect was raw, askew, handmade—a primitive-looking object that recalled African shields, Polynesian navigation devices, Spanish devotional objects, and bones that have broken through the surface skin.” (Richard Marshall, “Repelling Ghosts,” in Exh. Cat., Malaga, Palacio Episcopal de Malaga, Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1996, p. 140)

Emblazoned with frenzied, gestural marks and urgent annotations that reflect the spontaneity of graffiti, Santo 4 is a significant milestone in the inauguration of Basquiat’s certified status as an international art star. It is universally acknowledged that 1982 was the most significant year in the artist's tragically short yet enduringly prolific career. Painted in this seminal moment and belonging to a small number of captivating works created on roughly hewn canvas supports, Santo 4 is a preeminent articulation of Basquiat’s expressionistic force, adept combination of cultural references and impactful iconography.

Created the year after Basquiat’s breakthrough participation in the now-legendary New York/New Wave exhibition at the P.S.1 Contemporary Art Centre, Santo 4 is the perfect encapsulation of the artist’s transition from street to studio. Whilst self-organized exhibitions such as the Lower Manhattan Drawing Show at the Mudd Club gave crucial exposure for the artist, his breakthrough participation in the P.S.1 show and success in the show Public Address at the Annina Nosei Gallery gave him the critical success that was to bring about a huge turning point in his career. Indeed, it was in this year that Nosei became Basquiat's primary dealer and staged a critically acclaimed solo show of the artist's work. Using Nosei's Prince Street gallery basement as his studio, Basquiat forged influential links with Bruno Bischofberger and Larry Gagosian. Subsequently, his rise to stardom was astoundingly accelerated: exhibited alongside Gerhard Richter, Joseph Beuys, and Cy Twombly he became the youngest artist to have ever participated in Documenta in Kassel, heralding 1982 as the definitive year in his sudden yet pervasive invasion of the art world. Looking back on this astonishing year, Basquiat recalled, "I made the best paintings ever." (Jean-Michel Basquiat cited in Richard Marshall and Jean-Louis Prat, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Paris 2000, p. 202)

Not only did 1982 bring about extraordinary critical success for Basquiat, it also saw the birth of a celebrated corpus of works stretched over jutting corner supports and exposed stretcher bars. Basquiat and his assistant at the time set about crafting stretchers and frames out of a whole host of found materials such as carpet tacks, rope, canvas and wooden mouldings. Insouciant and purposefully rudimentary, these structures physically dismantle and imbue the grand tradition of painting on canvas with the tribal and primitive, while also referencing a grander art historical tradition of assemblage and collage most influentially advanced in postwar American art by figures such as Robert Rauschenberg.

While the evocation of primitive art very much alludes to Basquiat’s ethnic heritage - born to Puerto Rican and Haitian parents and brought up in Brooklyn, Basquiat's art habitually draws on his triangular cultural inheritance – the artist was also intensely influenced by Picasso for whom primitivism was an antidote to the conservatism of the academies. Similarly, Basquiat finds in primitivism a correlative mode for expressing an overtly contemporary angst simultaneously tied to his own racial identity and his position as an artist responding to the cool minimalism that permeated the gallery scene in Manhattan during the early 1980s.

Dominated by a large skeletal figure surrounded by a medley of scribbled marks and scrawled annotations – emblematic of Basquiat's polemic urban iconography – Santo 4 is demonstrative of the very best of the artist’s celebrated practice. His use of the iconic skeleton motif is both formally and symbolically crucial. Whilst the skull acutely references modernist abstraction and Picasso’s engagement with African art, it also engages with Basquiat’s own identity as a black subject seeking expression within a seemingly ‘white-washed’ art world. As surmised by cultural theorist Dick Hebidge "… in the reduction of line into its strongest, most primary inscriptions, in that peeling of the skin back to the bone, Basquiat did us all a service by uncovering (and recapitulating) the history of his own construction as a black American male." (Dick Hebidge, ‘Welcome to the Terrordome: Jean-Michel Basquiat and the Dark Side of Hybridity’, in Exh. Cat., New York, Whitney Museum of American Art, Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1993, p. 65) Reduced to its skeletal framework the figure also purports Basquiat’s scientific interest in the anatomical makeup of human beings, a subject that had fascinated the artist from an early age. His mother gave him a copy of Grays Anatomy, when, after being hit by a car at the age of seven, he spent a month recovering in hospital. The anecdotal genesis of this interest was further substantiated when Basquiat discovered Leonardo da Vinci's pioneering studies of the human body. Furthermore, the rich assemblage of caricatured faces, arrows and scribbled phrases, which include a childlike sketch of an airplane in the left centre of the composition, recalls the urban iconography of the artist's SAMO days. Ubiquitous to the metropolitan environment of New York, crudely articulated images of cars and planes recur throughout his early work. Along with the words Tokyo, South Korea and Peking, the plane contributes to the global mood that pervades the present work and concurrently symbolises the artist’s growing international success.

Rife with Basquiat’s rich, multi-faceted iconography, Santo 4 imports a dense narrative steeped in symbolic potency. Belonging to Basquiat’s trailblazing group of stretcher paintings, it reflects the nascent global excitement surrounding the artist at the time and acts as a bold proclamation of his inauguration into art history. Rene Ricard, one of the artist’s most notorious critics, singled out this revolutionary body of work and proclaimed: “For a while it looked as if the very early stuff was primo, but no longer. He’s finally figured out a way to make a stretcher… that is so consistent with the imagery… they do look like signs, but signs for a product modern civilisation has no use for.” (Rene Ricard cited in Phoebe Hoban, Basquiat: A Quick Killing in Art, London 2008, p. 105)

Jean-Michel Basquiat IN THE WINGS

“Jean-Michel began to incorporate the names of these songs and the linear notes of the records, and mesh those words with images in his painting…He immortalized those records in a way that blended with his style and was very much a part of where he was coming from. But always with a twist and sense of humor.” (Fred Braithwaite, “Jean-Michel as Told by Fred Braithwait a.k.a. Fab 5 Freddy, An interview by Ingrid Sischy,” in Exh. Cat., Malaga, Palacio Episcopal de Malaga, Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1996, p. 155)

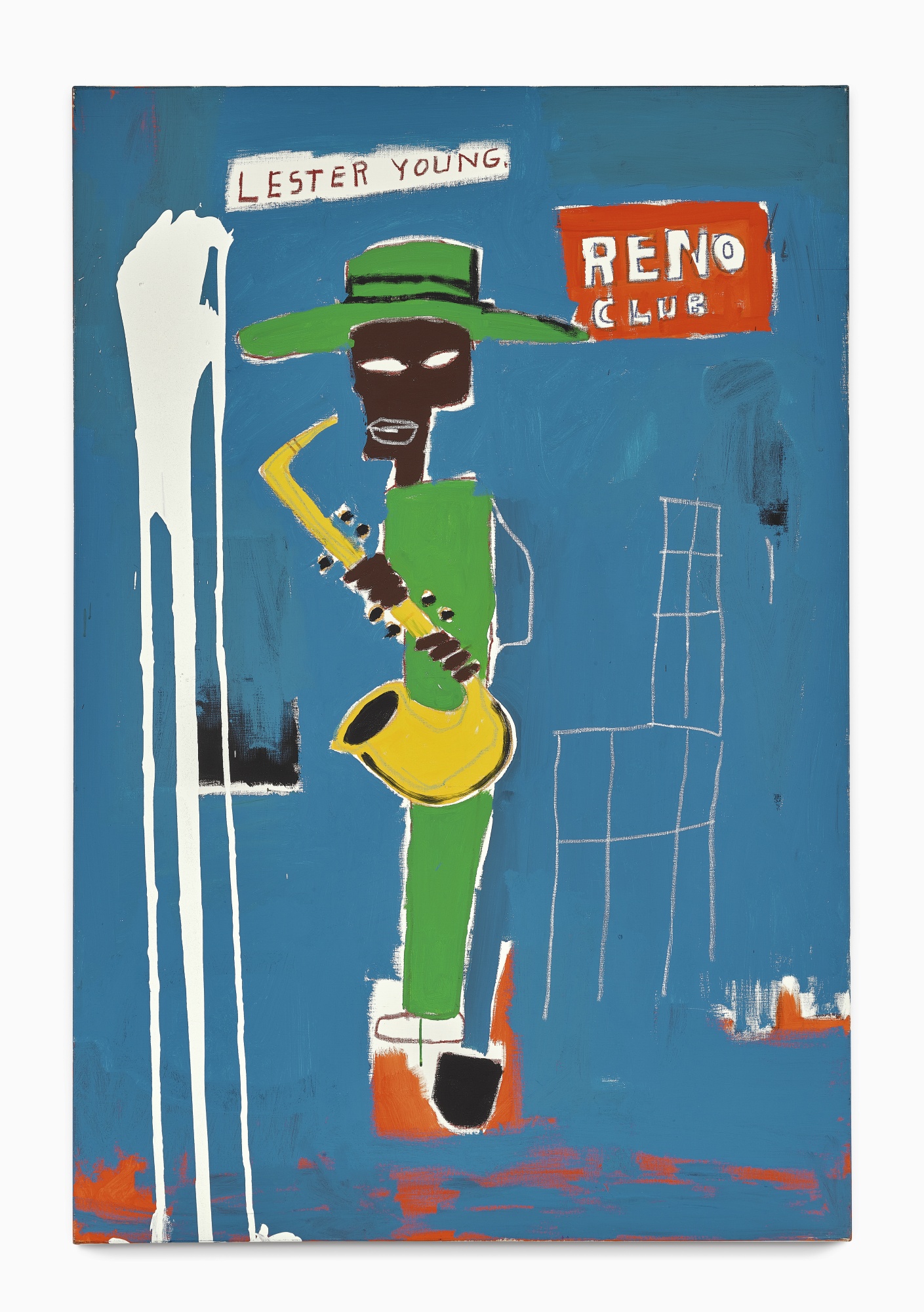

Painted in the crucial moment of 1986, just two years before his untimely death, Jean Michel Basquiat’s In the Wings is undoubtedly one of the most charismatic cultural portraits of his entire oeuvre. Adding to the limited number of important paintings that he dedicated to the greatest jazz legends of the Twentieth Century, here Basquiat enshrines the image of Lester Young – arguably the most influential and innovative saxophonists of all time – and creates a highly personal, devotional icon for posterity. Beyond paying homage to his musical idol, Basquiat instigates a cross-generational synthesis of artistic volition as the fluidly improvisatory tones of Young’s radical jazz are given a perfect visual counterpart in the painter’s unique gestural flare. Bearing a relatively pared-down composition, an enigmatic blue background and by focusing on a single African-American figure, In the Wings is stylistically emblematic of the important set of works created in the final years of Basquiat’s career in which he focused more heavily on Black subjects. By inducting Lester Young into his great pantheon of Black cultural icons, Basquiat seeks to reshape narratives on African American culture, whilst simultaneously positioning himself as contributor to its great legacy. Having acknowledged himself as a relative rarity as a Black artist within a racially homogenous art world, through In the Wings Basquiat destabilizes the canon of cultural history by inserting Black consciousness at its forefront and chiefly positioning himself as its visionary narrator.

From famous athletes such as Sugar Ray Robinson, Cassius Clay, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, to political figures including Malcolm X and Marcus Garvey, Basquiat’s oeuvre is punctuated by emphatic references to ground-breaking African American figures of the 20thcentury. Reverentially valorizing their successes in the face of staunch adversity and extreme racial prejudice, the historic development of American jazz music became Basquiat’s third arena in which to explore the rich and influential products of Black culture. Such as in the 1983 work Horn Players, now in the collection of the Broad Museum in Los Angeles, from early in his career Basquiat celebrated what Bell Hooks has described as "the innovative power of black male jazz musicians, whom he reveres as creative father figures," later proceeding to depict significant musicians such as Charlie Parker, Dizzie Gillespie, Ben Webster, Duke Ellington, Max Roach, Billie Holliday and Lester Young. (Bell Hooks, 'Altars of Sacrifice: Re-membering Basquiat' in Outlaw Culture: Resisting Representations, New York, 1994, p. 35) Painted in the same year and bearing the same blue backdrop as the present work, King Zulu (Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art) is another work also dedicated to a founding feather of American Jazz, Louis Armstrong.

From the 1950s, as a predominately African American Art form, Be-bop Jazz revolutionized the trajectory of music by privileging a highly expressive and improvised approach that finds a replete parallel in Basquiat’s painterly freedom. With individualism and experimentation at the heart of jazz music, each of Basquiat’s jazz heroes maintained a distinctive vocal or musical style, making unique artistic contributions to the development of the genre. Starting as an innovative member of Count Basie's band in Kansas City in the mid 1930s, Lester Young is one such figure who redefined jazz through his sensual refinement of Swing music. In the present work, Basquiat ultimately mirrors the relaxed tone and sophisticated harmonies that set Young’s music apart from his contemporaries in the supreme formal balance that also retains a sense of energetic improvisation. Compared to the densely frenetic compositions of the early 1980s, here we see a wise and confident Basquiat carefully selecting references and techniques – marrying style and content – to offer a highly particular vignette.

Young was well known for the unorthodox manner in which he positioned his saxophone as he played. Emerging from a brilliant blue backdrop, Basquiat privileges this detail with the contrasting yellow glare of the centralized instrument. Grasped by the dandyishly styled Young in a vibrant green suit and wide-brimmed hat, the charismatic musician is spot-lit and center stage in the composition. Surrounded by the stupefying abstract rhythms of the artist’s brush, a visceral cascade of gestural white paint down the left edge of the picture provides a synesthetic evocation of free flowing sound. Yet, whilst the canvas chimes with the exuberance of a live performance, Basquiat’s use of text and his characteristic insistence on two-dimensional depiction seems to intimate a promotional poster or perhaps a record cover, as his immediate frame of reference. Having died in 1959, Basquiat’s evocation of the “Reno Club” refers to an original live recording made there in Kansas city in 1936; one of the many Jazz records that provided an inspirational score against which his distinct subjective visions were created. Basquiat’s expedient rise to success had come through his fresh presentation of a diverse mélange of cultural influences, from graffiti tags to comic books and even food packaging. Here he simplified his unique symbolic lexicon to focus on one favored moment in the history of jazz.

Whilst Lester Young was known for having popularized much of the jazz ‘hipster jargon’ associated with the genre, here Basquiat evades his own characteristically ambiguous use of words, privileging instead their ability to designate the specific moment. This open stage allows Basquiat to bathe his central icon in a fittingly lyrical abstraction that shows the full range of his transcendent technique as both a painter and draughtsman. As Robert Farris Thompson describes, Basquiat consciously enters into a nuanced dialogue with his painterly predecessors: "Basquiat himself did not parody Abstract Expressionism, as Pop Masters sometimes did. As he fused his sources, his mood was more complex: humour, play, mastery, and stylistic companionship. He brought into being first-generation (Kline) and second-generation (Twombly) Abstract Expressionist citations and mixed them up amiably with cartoon, graffitero, and other styles." (Robert Farris Thompson, 'Royalty, Heroism, and the Streets: The Art of Jean-Michel Basquiat' in Exh. Cat., New York, Whitney Museum of American Art, Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1992, p. 36) Whilst the luscious drips of free-flung white provide a nod to Jackson Pollock, the whimsically minimalist scrawl of the white squares that suggest a chair seem to toy with the authority of the minimalist grid, promulgated by Sol LeWitt, Donald Judd and Agnes Martin. Invigorating the background with a static red that demarcates form and bleeds through in the manner of both Robert Motherwell and Clyfford Still, Basquiat usurps the authoritarian schools of painting that dominated American art until his arrival upon the New York scene, whilst responding to the revolutionary aural experience of Young’s music.

Crucially, Basquiat’s highly abstracted treatment of Young’s face brings to light the intersection of race, representation and culture that underscore the painting. Composed of a rich mahogany brown, the highly stylized eyes and naively emphasized lips take a dually provocative role by recalling both the resounding influence of African art on modern masters such as Picasso, as well as the unsettling aesthetics of minstrelsy and the archaic racial stereotypes that once permeated American visual culture. As surmised by cultural theorist Dick Hebidge "… in the reduction of line into its strongest, most primary inscriptions, in that peeling of the skin back to the bone, Basquiat did us all a service by uncovering (and recapitulating) the history of his own construction as a black American male." (Dick Hebidge, "Welcome to the Terrordome: Jean-Michel Basquiat and the Dark Side of Hybridity," in Exh. Cat., New York, Whitney Museum of American Art, Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1993, p. 65) In his tribute to Lester Young, on one level Basquiat gives aesthetic form to the revolutionary rhythms of jazz as a means of celebrating the legacy of Black culture and the historic achievements of Black artists. However, in also considering African American identity at the intersection of personal experience and a set of performative masks, he has immortalized his own subjectivity within the canon of cultural consciousness.

Joan Mitchell- NO ROOM AT THE END

“In terms of sheer largeness of vision, of solving painterly problems with an almost incredible audacity, these oversize pictures from the 1970s have few rivals in all of modern American painting…It can be argued that these works mark Mitchell’s ascendancy to a level that few artists have attained, an achievement that would set the stage for her work to come” (Jane Livingston, ‘The Paintings of Joan Mitchell’, in: op. cit., 2002, p. 35)

Triumphantly heralding an irrepressible joie de vivre, No Room at the End is an arresting testament to the visual dynamism and profound emotive force of Joan Mitchell’s inimitable painterly oeuvre. A magnificent example of her commanding paintings of the late 1970s, the densely layered surface of the present work powerfully evokes the lush countryside of the artist’s home in Vétheuil, engulfing the viewer in a sensory tide of blooming countryside. Simultaneously, coursing across the monumental dual canvases, Mitchell’s impassioned strokes reveal an emotive intensity that transforms the riotously abstract painting into a vessel of profound self-expression. Reflecting upon the intimately personal nature of Mitchell’s practice, poet Nathan Keman notes that Mitchell’s paintings reveal an “attention to the most fleeting sensations; to her feelings; to remembered images of landscape, which she carried with her and which she re-visualized as marks made on canvas.” (Exh. Cat., New York, Cheim & Read, Joan Mitchell: The Presence of Absence, 2002, n.p.) A visual tour-de-force of color, gesture, and exhilarating painterly bravura, No Room at the End is wholly demonstrative of an artist at the apex of her expressive painterly abilities.

Executed on a truly monumental scale, No Room at the End constitutes a remarkable sensory engagement with the artist’s beloved countryside home in France. Founded in a visionary love of nature, combined with a painterly idiom rooted in abstraction, Mitchell’s oeuvre forged a conceptual union between the gestural canvases of the American Abstract Expressionists and the profoundly rich painterly idioms of the European Impressionists. Although Mitchell spent the first years of her career as a female painter within the predominantly male New York School, her relocation to Paris in 1959, then to the countryside of Vétheuil in 1968, afforded her the critical conceptual distance and creative freedom to create her own, utterly unique artistic practice. The artist’s home, surrounded by an expansive garden in which Mitchell planted sunflowers and other vibrant blossoms, brought an inimitable sense of joy to the paintings she executed between 1968 and the late 1970s. Mitchell’s biographer Patricia Albers declares, “From the time she acquired Vétheuil, its colors and lights pervaded her work. Loose allover quilts of limpid blues, greens, pinks, reds, and yellows… fairly burble, their colored lines and shapes registering a painter’s fast-moving hands as they rise steeply, floating between inner and outer worlds, to jostle and bank at their tops.” (Patricia Albers, Joan Mitchell: Lady Painter, New York, 2011, pp. 313-314) The abundant natural beauty of the French countryside is powerfully embodied in the vigorous layering of dense, jewel-toned pigment in the present work; rendered with an energetic gestural gusto, lush swaths of sunflower yellow, shimmering blue, and a subtle, earthy orange bloom across the monumental canvas to surround the viewer in the fragrant atmosphere of a springtime garden. The result is a composition evocative of the painterly abandon of de Kooning, the luminous vibrancy of Francis, and the exquisite specificity of Monet.

In their unapologetic vitality, Mitchell’s monumental works of the 1970s number among the most striking and painterly examples of the artist’s career. The sheer size of the present work, which spans almost twelve feet in width, testifies to the confidence and ambition of Mitchell’s artistic practice following her move to Vétheuil; indeed, unlike her Frémicourt studio, where oversized canvases had to be rolled in order to enter and exit the space, therein preventing the artist from covering her canvases in layers of sumptuous impasto, the high-ceilinged workspace in Vétheuil afforded the artist ample room to execute her towering theses on abstraction. While Mitchell’s earlier paintings interspersed vivid pigment with areas of blank canvas, the lush density of the present work is echoed in other monumental paintings of the same year, such as Rosebud, in the collection of the Albright-Knox, and Posted, held by the Walker Art Center; prefiguring her celebrated La Grande Vallée series of the early 1980’s, Mitchell’s swift, vigorous and thick mark-making in these paintings culminates in a luminous and buoyant image. Jane Livingston aptly reflected on this decisive transition in the artist’s oeuvre: “In terms of sheer largeness of vision, of solving painterly problems with an almost incredible audacity, these oversize pictures from the 1970s have few rivals in all of modern American painting… It can be argued that these works mark Mitchell’s ascendancy to a level that few artists have attained, an achievement that would set the stage for her work to come.” (Exh. Cat., New York, Whitney Museum of American Art, The Paintings of Joan Mitchell, New York, 2002, p. 35)

Consistent with Mitchell’s celebrated work of the 1970’s, the mesmerizing mixture of thick, emotive swathes of paint and looser, more spontaneous drips and strokes exhibited in No Room at the End suggests a corresponding progression towards greater emotional depth on the part of the artist. Noting this shift in the artist’s oeuvre, Klaus Kertess notes, “In 1975, Mitchell began to blur and bury the rhythmic rectangularity of her work in a heavily impastoed opacity, and then released an unremitting rain of strokes that engulfed most of her paintings, through 1984, in a passionately pulsing ‘alloverness.’ The larger size and scale mastered in the first half of the seventies now acquired greater visual and emotional depth. As she reached the age of fifty, her sense of wonder in nature not only remained intact but continued to expand, while her fear and rage at human loss had hardly subsided…Mitchell’s paintings now took on the full ripeness of maturity; furious intimacy gave way to a fuller understanding that her aloneness was as universal as it was uniquely personal. Her remembrances became more sonorous and varied.” (Klaus Kertess, Joan Mitchell, New York, 1977, pp. 34-35) Underlying the luminous blues and yellows of the present work, Mitchell’s thick black strokes instill No Room at the End with the poignant rhythm of experience, grounding the otherwise effervescent composition in maturity. In her unrepentant emphasis upon mark, each stroke retaining its autonomy whilst corresponding to a larger cohesive image, Mitchell’s canvas recalls the psychical intensity of van Gogh’s landscapes of the 1880’s. Of Mitchell, Kertess notes, “From painting to painting, there was a greater variety of color, mood, and format. The indivisibility between the strokes as a unit of visual structure and the stroke as a unit of intertwining natural and emotional forces reflects the influence of van Gogh, the powerful directness of his mark making that merged the seen with the felt.” (Klaus Kertess, Joan Mitchell, New York, 1977, p. 35) This intensification of emotive and painterly force is exemplified in No Room at the End as, in a joyful comingling of hues and texture, Mitchell renders the lush vibrancy which surrounded her; it is as if the sumptuousness of both sentiment and pigment has exceeded the canvas’ ability to hold them and they have burst free, coursing down the canvas face in a rain of pictorial dynamism.

Jean-Michel Basquiat "ANTAR"

“He reproduces on the canvas the abstract figural power of his experience, the declarative and narrative temperament, the explicit and didactic strength, the confused condition and the spontaneous aggression of visual elements.” (Achille Bonito Oliva in Exh. Cat., Naples, Castel Nuovo, Basquiat in Naples, 1999, p. 25)

In its dominating scale, compositional intensity, expressionistic force, and deft engagement with art history, politics and race, Antar is demonstrative of the very best of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s celebrated practice. Masterfully distilling the quintessence of socio-cultural concerns and vibrant stylistic techniques, Antar utterly characterizes his works of the mid-1980s. The present work calls forth elaborate iconographies from ancient cultures, with primitive sculptures, masks and a canoeing tribal figure encircling a savage mythical creature, wielding a bloodied spear. Referencing the mythical figure of Antar, the pre-Islamic Arabian knight and poet whose legacy as a warrior and intellectual is recounted throughout Arabic literature and visual arts, Basquiat draws on a host of pre-historic references to paint an expansive canvas rich in symbolic imagery and allegorical content. Via an astounding pluralistic command of art historical vernacular that synthesizes graffiti, primitivism and Abstract Expressionism, Basquiat presents a powerful racial dialectic as a palimpsest of post-modernity. Indeed, such intense erudition is authoritatively delivered by an unsurpassed magnificence of surface manipulation. Streaming drips of acrylic and viscous clumps of oil stick lyrically coalesce to create an exuberant and formally stunning masterwork that posits Antar among the most painterly of Basquiat's entire production.

Antar was created at a moment when Basquiat had reached an absolute pinnacle of celebrity and recognition, following his rapid rise to artistic prominence in 1981 when his works were first exhibited in public. Born into a regular working family in Brooklyn, New York, at the age of seventeen Basquiat dropped out of school and moved to Manhattan’s spirited Lower East Side. With few resources other than sheer determination, within just four years the young artist progressed from intermittent bouts of homelessness and the ubiquitous dissemination of his ‘SAMO’ graffiti tag across the city, to being introduced to an enamoured art world as ‘The Radiant Child’ through René Ricard’s seminal Artforum article of December 1981. Represented in 1985 by two of the leading gallery owners of the day, Bruno Bischofberger and Mary Boone, Basquiat’s paintings attracted almost hysterical acclaim when exhibited, and seemed to epitomise the cultural zeitgeist of 1980s New York, a city unabashedly dominated by conspicuous consumption. Basquiat’s dominance and conquest of the New York art world was reinforced by his presence on the cover of ‘The New York Times Magazine’ on February 10 1985, accompanied by an effusive article written by Cathleen McGuigan. McGuigan declared: “The extent of Basquiat’s success would no doubt be impossible for an artist of lesser gifts. Not only does he possess a bold sense of colour and composition, but… he maintains a fine balance between seemingly contradictory forces: control and spontaneity, menace and wit…” (Cathleen McGuigan cited in Exh. Cat., New York, Whitney Museum of American Art, Jean-Michel Basquiat, p. 246) McGuigan’s reference to ‘menace and wit’ appears particularly apposite in the case of Antar, in which the seemingly threatening nature of the facial expressions of the red eyed mask and ferocious mythical beast are brilliantly countermanded by the element of humor conveyed by the floating canoeing man whose face is plastered with an unerring grin.

In many ways, Basquiat’s extraordinary reinterpretation of figuration represents a critical retort to the intellectualized currents of Minimalism that permeated the Manhattan gallery scene during the early 1980s. Basquiat explained in 1985: “The art was mostly minimal when I came up and it sort of confused me a little bit. I thought it divided people a little bit. I thought it alienated most people from art.” (Jean-Michel Basquiat cited in Exh. Cat., Basel, Fondation Beyeler, Jean-Michel Basquiat, 2010, p. XXIII) Basquiat forged an aesthetic that combined a Pop integration of comic book imagery with gestural abstract passages very much attuned to a contemporaneously outmoded high-art language of Abstract Expressionism. Possessing a sophisticated knowledge of art history Basquiat infused his painting with a defined instinctual understanding of the language of abstraction. In the present work forceful painterly strokes are deployed with an assured command, over which layers of erased, painted over and liberally confident mark making recast an innovative symphony of abstract expressionism’s pictorial vernacular. Basquiat commands, combines and synthesizes these paradigms of American art with spectacular faculty: the schematic background, great swathes of deep blue, red and green are laid down with intense, gestural brushwork. The artist's brute force of application and layering of paint and line through brush and oil stick confers a remarkably paroxysmal yet deliberate harmony via a structural and exuberant formalism. There is no spatial recession or perspectival logic to the composition; form and ground mesh together to confer an implosion of form to pure energy. Imbued with the frantic exertion and the poured, dripping aesthetic of Jackson Pollock; combined with the exuberant colorism and dramatic painterly gesture of Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline, Basquiat's grasp and deployment of Twentieth Century American art history is impressive and manifold. With the present work, Basquiat deftly weaves the machismo painterly attitude of Kline in the expansive and expressive gestural blue background with ethereal Twombly-like ciphers of line.

Of Puerto Rican and Haitian descent, and raised in Brooklyn, Basquiat drew from his manifold ancestral background and racial identity to forge a body of work acutely conscious of his contribution to the meta-narrative of an almost exclusively white Western art history. Basquiat aligned himself stylistically with Picasso, for whom primitivism was an antidote to the conservatism of the academies. Painterly elements extrapolated from the early Twentieth-Century master’s canon of abstraction and treatment of line thread a course throughout his oeuvre. Spanning Picasso’s Cubist undoing of the figure, through to the ground-breaking African Period, Basquiat masterfully quotes and re-appropriates. In the present work, such a reading is certainly at stake within the twisting application of line and stuttering dynamism of its composition, whilst, the mask-like figure undoubtedly evokes the kind of tribal masks apparent in Picasso’s masterwork, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) and his abstracted Self Portrait (1906). Basquiat found in primitivism a correlative mode for expressing an overtly contemporary angst tied to his own black identity, embodying his projected “blackness,” while subverting these very identity constructions by emulating Western conventions of painting.

Sophisticated, confident and radiating a conviction of artistic vision, the extraordinary visual power of Antar is a sheer testament to the thriving talent of a young and brilliant artistic spirit who, by 1985, had truly secured his position at the vanguard of an artistic consciousness. The present work solidified Basquiat as a figure who dashed effortlessly between art historical precedents in order to create a wholly individual painting deeply suffused with personal history, memory and emotion.